Road to Sachsenhausen

“It seemed as impossible to conceive of Auschwitz with God as to conceive of Auschwitz without God.”

— Elie Wiesel, 1986 Nobel Peace Prize lecture

On my way from central Europe to Scandinavia last week, I stopped off in Berlin to visit for the very first time the former beating heart of Hitler’s Germany. How could anyone of my generation not? If you happened to be born in America in the middle of the 20th Century (say between 1940 and 1960) the history you absorbed as a child — in school, on TV, at drive-in theaters — was replete with images and stories of Nazi Germany, and that continued well into adulthood. From Victory at Sea to Judgement at Nuremberg. From Sound of Music to Sophie’s Choice. From The Great Escape to Schindler’s List, Germany was on our minds.

For me Berlin was the attraction. But I’d heard too that on the edge of town, in the sleepy bedroom community of Oranienburg, there still stood the remnants of a former Nazi concentration camp, one most Americans have never heard of. Its name was Sachsenhausen. And from the day it was covertly built by Nazi SS (Gestapo) chief Heinrich Himmler in the summer of 1936 — the very same summer Berlin was otherwise happily hosting the Olympic Games — it fulfilled a very special purpose, serving as the camp next door to the national SS headquarters and as a model and laboratory for all the Nazi death camps to come, from Dachau to Auschwitz.

I intended to visit Sachsenhausen, but not immediately. First I wanted to see Berlin on a larger canvas with all its history — from its origin as a fish camp for Slavic-speaking pagans in the Middle Ages to its surprisingly late (18th century) start as a town to its central role as capital city of all of Germany’s recent iterations (Kingdom of Prussia, 1701-1871; German Empire, 1871-1918; Weimar Republic, 1918-1933; Third Reich, 1933-1945) — to everything after that, including the here and now.

And I did.

I saw blues clubs that seem to value the African-American experience even more than a lot of Americans do. I saw handsome parks while strolling Unter den Linden and picnicking in the Tiergarten. I saw one of Berlin’s world-famous museums, including a current exhibit of Queen Nefertiti and early-Egyptian artifacts. I saw the glass dome of the remodeled Reichstag — the national capitol — meant to convey both the transparency of a true democracy and also a new relationship in which government leaders (seated at the bottom of the dome) are subservient to the public (touring and observing from above). Nice, I thought. We could use that in Juneau.

I also saw remnants of the famous wall that divided East and West Berlin during the Cold War years that followed World War II. What initially prompted its construction (according to the guide on what I thought was an excellent Berlin history walking tour), was the sheer unpopularity of living in Stalin’s and later Krushchev’s eastern sector as compared to Eisenhower’s and later Kennedy’s western sector.

When Stalin died in 1953, my guide said, Soviet-appointed leaders in East Germany passed severe new work quotas that both increased hours and reduced pay for all the Germans living on the eastern side of the border, including the eastern side of the geo-political island of Berlin. German workers responded by staging a national strike. Soviets responded by sending in 15 Russian tanks that opened fire on the workers. The guide said about 200 East German strikers were killed that day, including about 50 in Berlin.

That became a threshold moment that lost the hearts and minds of most East Berliners for good, and they began to find their way across the barbed-wire border in greater numbers each day, voting with their feet. Soviet authorities countered by installing a series of inspiring public murals on their side of the border portraying how happy the working class had actually grown under Communist leadership.

When that didn’t seem to work, in 1961, they erected a wall three and a half meters high that even famed Russian high-jumper and world-record holder Valery Brumel couldn’t scale. It wasn’t to imprison East Berliners, the Communist authorities explained. It was an “anti-Fascist protection barrier.”

By any name, it failed to endear itself to East Germans, who continued to find clever ways to breach the wall, sometimes by means as daring as hot air balloons and zip lines. Still, it stood in place for 28 years. Until Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev — in the dawning days of the Information Age in the late 1980s — finally began to grant his people new freedoms. Which delayed but didn’t prevent the ultimate collapse of East Germany and the historic dissolution of the Soviet Empire a few years later.

Now all that’s old history too. Nearly a quarter century has passed since “the fall of the wall.” I was told that about half of the people living in Berlin today never even experienced the Soviet occupation, let alone that ugly period earlier when a mad man led their nation for 12 long years.

What they know is a vibrant, creative, new-millennium Germany with no Army and some of the most peace-loving citizens in Europe. Of course Germans vary as much as any other people, and regions within Germany vary too — from the prosperity of the politically conservative South I observed near Munich to the urban energy (and unfortunately longer unemployment lines) of the liberal North I saw in Berlin.

But I will go out on a limb here by saying Germans seemed to me to be more willing to publicly acknowledge the darkest days of their own history, including the Holocaust, than my own country is in terms of the lasting devastation of America’s original sin of slavery and racism. (Or as American author and Nobel Prize for Literature winner Toni Morrison once put it in an interview: “If Hitler had won the war and established his ‘Thousand-Year Reich’ … the first 200 years of that reich would have been exactly what that period was in this country for Black people.” I think you can quibble with her “exactly,” but not with her point.)

But I will go out on a limb here by saying Germans seemed to me to be more willing to publicly acknowledge the darkest days of their own history, including the Holocaust, than my own country is in terms of the lasting devastation of America’s original sin of slavery and racism. (Or as American author and Nobel Prize for Literature winner Toni Morrison once put it in an interview: “If Hitler had won the war and established his ‘Thousand-Year Reich’ … the first 200 years of that reich would have been exactly what that period was in this country for Black people.” I think you can quibble with her “exactly,” but not with her point.)

In Berlin, I saw Germany’s own dark chapter laid bare all over town:

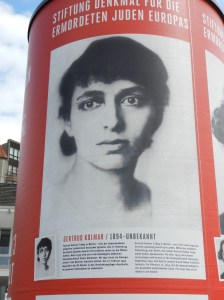

In the haunting city-center Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, with it’s labyrinth-like rectangular columns that gradually grow taller and more menacing as you venture toward the center.

In the silent memorial opposing state censorship (simply, empty bookshelves) in the spot outside a university where Marx studied and Einstein taught — and Nazis very publicly burned 20,000 books they considered either subversive or impure.

In posters commemorating 2013 as the 80th anniversary of the Nazi regime’s accession to power — and the 75th anniversary of the anti-Jewish pogroms of Kristallnacht — in a Berlin government-sponsored initiative titled “Diversity Destroyed.”

And finally in the brochures advertising train tours to Sachsenhausen.

***

From the station in Oranienburg, we walked a couple miles down oddly unremarkable suburban streets to a field at the edge of town. There was a path there that led to the Sachsenhausen visitor center, which had a book store and a wash room and a door that led outside again. From there we walked along the camp’s outer wall to a courtyard with a guard tower and underneath it the Sachsenhausen sentry gate — still engraved with the once-universal Nazi message to new prisoners: “Arbeit macht frei” — “Work will make you free.”

The tour started slowly, incrementally. First we entered one of the last remaining barracks — there were once 68 like it, each housing up to 400 prisoners in a space suitable for one tenth that number. Prisoners slept there in three-decker bunk beds, sometimes two or three to a bed.

Each barracks contained seven or eight toilets, which created huge traffic jams in the morning when several hundred prisoners needed to use them at once. And if you missed that opportunity, you wouldn’t get a second chance until end of day, our guide told us. Above all, however, you didn’t want to miss the morning roll call, because the penalty for doing that was severe.

Roll call was held in front of the main entrance machine gun tower, which our guide said had “pan-optic vision,” thanks to the camp’s deliberate triangle shape. When a new prisoner arrived he or she was given a number, and that became their new identity. At roll call you needed to recite your number in perfect text-book German before you could be released, a feat that was especially difficult for foreign prisoners who didn’t speak Deutsch.

One infamous Sachsenhausen roll call was conducted in freezing weather in the winter of 1940 by Rudolph Hess, our guide told us. It droned on all day. Prisoners standing in place eventually began freezing to death. Some fell to the ground with the onset of hypothermia. Dozens more died during the night. By the following morning, according to Nazi records, 140 prisoners had perished.

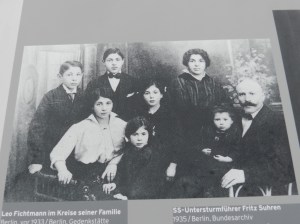

During the 10 years it functioned as a Nazi concentration camp, Sachsenhausen served as a destination for a wide variety of prisoners — about 200,000 in all.

If you were ordered to wear an inverted red triangle on your shirt or coat, that meant you were a “political prisoner,” which might include virtually anyone who opposed the Nazi regime — from journalists to clerics to outspoken liberals and Communists.

If you wore an inverted black triangle you were a “social prisoner,” which meant you were either unemployed, or an alcoholic, or a homosexual, or a prostitute, or a Gypsy or anything Nazis considered anti-social. If you wore a blue triangle you were simply an emigrant, a non-German. If you wore a yellow triangle that meant you were a Jew.

(Our guide tried valiantly for about 15 minutes to explain the backstory of anti-Semitism in Europe, from early Christianity on, including the ghettoization of Jews that began around 1200 AD, the slurs about “Christ-killers,” the urban-legend of the blood libel, the manner in which Jews, even as late as the 20th century, became the default scapegoat for nearly anything that went wrong. Like the loss of territory Germany suffered in the Treaty of Versailles at the end of World War I. Then the hyper-inflation and staggering unemployment and long soup lines that followed with the Great Depression. Jews and Communists were to blame, Hitler said, and many of the least educated Germans believed him. After rising to power in 1933, Hitler managed to pass laws that prohibited Jews from working in several occupations, or attending certain schools, or using public parks and swimming pools. From then on they were a moving target for Hitler’s stormtroopers. Then came Kristallnacht, the bloody pogrom of 1938 that rounded up Jewish entrepreneurs, broke their windows and set their shops on fire…)

Right after Kristallnacht, about 6,000 new Jewish prisoners were admitted to Sachsenhausen, according to the camp’s official history. Jews there began to fill several of the barracks. By the fall of 1942, however, most of them were transferred to Auschwitz — as Jewish prisoners all over Germany were — by order of SS chief Himmler. There thousands were exterminated. Jews were murdered at Sachsenhausen too, as were thousands of Soviet prisoners of war. Executions usually occurred in a prison within the prison, a hidden place called Station Z where the Gestapo held sway. And that was the last stop on the tour.

There was a courtyard there with tall posts. Some of the prisoners scheduled for execution were simply handcuffed and hung by their wrists from the top of the posts, sometimes until they fainted from the pain, or arms tore from sockets. Then the Gestapo would drag the body to a manhole and drop it in, and place a slanted grate on top. And there the prisoner usually perished.

But in Station Z the Gestapo also maintained more efficient ways to kill prisoners, methods that weren’t as traumatizing to the elite cadre of officers who supposedly were going to father a master race once the war was over. One was an underground gas chamber complex, a prototype for others that would be introduced in the worst of the death camps in the last years of the war. According to Nazi records, its designers used Sachsenhausen to test different forms of gas to determine which was most effective.

Another was a firing squad room masquerading as a doctor’s office to set the prisoners at ease. Once they were brought inside, a pretend medic would check them for their vital signs, weigh them, then ask them to stand with their back against a wall under a measuring rod to check their height. Concealed behind the rod, however, was a firing device pointed at the back of the prisoner’s neck. With the push of a button behind the wall the prisoner tumbled forward dead.

According to camp records, in the fall of 1941, the Gestapo used the concealed shooting machine to execute over 13,000 Soviet prisoners of war — predominantly Jews and suspected Communist officials — in the single largest mass murder that would occur at Sachsenhausen. After they were shot, their bodies were taken to an adjacent crematorium and burned. Then their ashes were buried in an outdoor pit.

As the war finally wound down in April of 1945 — as Soviet and American troops marched ever closer to Berlin — Himmler ordered the camp evacuated. A census taken two months earlier determined there were close to 70,000 prisoners at both the main camp and its satellites. So thousands of the prisoners were summarily executed. Thousands more were transferred to other camps. But the largest group, about 33,000 prisoners, were ordered to join what came to be called the “death march” to the Baltic Sea. Though weak and starving, the long column of prisoners was forced by Gestapo guards to walk up to 25 miles a day. Thousands died along the way. More than half nearly made it to the ocean when, suddenly, their German guards disappeared, fleeing for their lives, as units of the Red Army and U.S. Army arrived to save them.

A long and complicated story to be sure, just as Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel suggested at the onset. I left Berlin thinking about what he said. I considered a corollary. That either there was no religion or there was too much religion in a world that could allow an Auschwitz — or a Sachsenhausen. You wondered. You really wondered.

Interesting informative post, George. I’m the daughter of a young German woman and American GI. My grandfathers fought each other in WWII, one an American, the other a conscript who wore the German (yes, Nazi) uniform. My father bringing home a “Kraut” some years later was awkward to say the least. I grew up speaking German and made regular visits to see my grandparents who lived in Luedenscheid. It wasn’t until 1975 when I was in high school that I went to Berlin, a place where the whole of German history unfolded in its architecture, monuments and stories. The Berlin wall was still up then and at the American Checkpoint Charlie, we saw haunting images of people who had tried to cross it .We paused to ponder the eternal flame monument, one that would burn until the wall came down. It did, in 1989, just after my grandfather passed away. We all lamented that he did not live to see the reunification of his country. Thanks for a reminder of that time. Lest we forget.

Thanks for sharing, Kaylene. Wow! Sometimes the world’s just amazing, right? (Wondering if your opposing grandfathers ever got together for Thanksgiving, which could have been very interesting…) I’m thinking too you must have had a fascinating childhood, moving back and forth from Europe to America. Cheers! And thanks for reading!

Very cool!! Juneau could use that.

Love ya dad

Sent from my iPhone

Love you too, Moll! (And thanks for reading!)

The memories I have of Germany from 30 years ago are not easily forgotten. Conversations with my fuel oil delivery neighbor, who marched into Russia with scant clothing for the conditions, and to lose his foot to frostbite. The gratitude of an older generation for an American presence, at least where we lived. And the haunting, eerie specter over a visit to Dachau that, to this day, is easily recalled.

You captured some of this essence in a remarkable way.

Thanks, Deb. I appreciate the feedback. I know I violated every canon of blog-journalism by allowing my post to surpass the three-paragraph mark. But I felt pretty strongly that I shouldn’t over-simplify the subject. And I’m glad it touched your memories. Cheers, rowing buddy!